|

| *****SWAAG_ID***** | 305 | | Date Entered | 03/11/2011 | | Updated on | 19/11/2011 | | Recorded by | Tim Laurie | | Category | Geographical Record | | Record Type | Botanical HER | | Location | Stainmore | | Civil Parish | Not known | | Brit. National Grid | | | Record Name | Stainmore | | Record Description | Relict Woodland on the Cliffs and Waterfall Ravines of Swaledale

Part One: Upper Swaledale

Work in Progress as at 31 October 2011

Introduction and Scope

This is a short introduction to a programme of current fieldwork designed to record the distribution of native tree species and woodland fragments throughout the River Swale catchment, west of Richmond.

My intention is to publish a full account of the fieldwork in due course . For comparative purposes, adjacent areas within Wensleydale and the Tees-Greta Uplands (Stainmore) are also included. The area of this survey is very large and with few exceptions has been confined to localities at or above the moorland edge. Woods wholly within improved pastures have been excluded. Thus, the scope has been confined to woodland localities on or clearly visible from CROW Access Land.

I have been concerned with the recording of Archaeological Landscapes throughout Wensleydale, Swaledale and the Swale-Tees/Greta Uplands (my study area) for almost 40 years and was introduced to the significance of ancient woodland in the Landscape by Andrew Fleming. It followed that no real understanding of the nature of early human activity in the Pennine Uplands (based on hunting and transhumance) was possible without consideration to the contemporary prehistoric woodland environment. In the absence of adequate pollen reports from Upper Swaledale I have recorded visible tree remains widespread at the base of blanket peat throughout the study area. (Laurie 2004). More recently, I have held the view that this would be best achieved with a detailed understanding of the composition and disposition of the native woodland communities which have developed on the differing soils derived from the abruptly changing rock strata of the area. (Rodwell, 1991. King C.A.M. in Millward 1988).

My purpose in undertaking this survey is to place on record the relict woodland vegetation at the remote waterfall ravines and on the extensive limestone cliffs of Swaledale and adjacent areas. These localities can be regarded as refugia for native trees and formerly more extensive woodland worthy of record on aesthetic grounds as the final refuge of specimen trees of great age, of individual character and of many different species. Each locality has unique botanical interest with plant communities reflecting different geology, aspect, aridity, accessibility and economic or, more recently, modification from planting schemes. Each woodland locality may include specimen trees which possess an individual sculptural quality which reflects their hard and long life. Although having enjoyed a fairly intense interest in upland flora throughout my life, I am not a trained botanist and could not achieve the aims of this survey without the assistance and active participation of Linda Robinson (LR), one of the BSBI Recorders for vc 65. LR has accompanied me on much of the fieldwork and all the credit for the botanical records must be assigned to her.

The Physical Background.

In Swaledale as elsewhere, very different woodland vegetation has developed in response to the soils derived from the abruptly changing rock strata - calcareous limestones succeeded by base poor sandstones and chert strata and from the glacial drift covered lower Dale Slopes.

Space does not permit an overview of the complex faulted Namurian strata of the study area and the reader is referred to Dunham and Wilson 1985. ‘Geology of the Northern Pennine Orefield.’ Vol 2 Stainmore to Craven Geological Survey. HMSO. The interpretation of the of the complex faulted geological strata from the 1:50,000 scale BGS Map: England and Wales Sheets 40 and 41 Solid and Drift Edition requires specialist knowledge.

Accordingly, the most basic categorisation of localities has been adopted here:

Type A: Localities on the predominantly siliceous strata of Namurian Age above the top of the Main Limestone.

Type B: As last but with local enrichment from strongly calcareous, tufa forming springs.

Type C: Localities on alternating limestone, sandstones and mudstone strata below the top of the Main Limestone.

Type D: Localities on the glacial drift covered hill slopes.

It follows that the soils and vegetation development at each of these localities is potentially very different, thus:

Vegetation at Type A and B locations is wholly or generally acidic and species poor, with local enrichment from tufa springs.

Vegetation at Type C and D Sites is potentially calcareous although leached soils provide the opportunities for local calcifuge communities.

Woodland vegetation at all localities can be modified by species selective extraction in connection with lead smelting and from lead mining operations.

Framework to the Survey

This is the first Part of a larger survey. For clarity the woodlands are to be described in six Sections within defined areas. Those within the Swale Catchment are to be described within Parts One to Four. For comparative purposes, woodland sites within the Ure Catchment (Wensleydale) are to be detailed within Part Five. Those to the north of Swaledale, and on Stainmore are detailed within Part Six.

These areas are further defined as follows:

Part One: Upper Swaledale comprising all sites within the catchment of the River Swale within the Civil Parish of Muker.

Part Two: Mid-Upper Swaledale, comprising the Swale catchment from the eastern limits of Muker CP down to the confluences of the Arkle Beck and Grinton Gill with the River Swale.

Part Three: Lower Swaledale, from the confluence with Arkle Beck downstream to Richmond.

Part Four North bank tributaries of the Swale comprising: the catchments of Clapgate Beck, Marske Beck, Arkle Beck, Barney Beck and Gunnerside Beck.

Part Five: Selected woodland sites within the catchment of the Ure.

Part Six: Selected sites within the catchment of the Tees/Greta (Stainmore).

The survival of native woodland on the limestone scars and in the waterfall ravines of Wensleydale differs from that of Swaledale and today does not include juniper and only very rarely, yew. Aspen is common at lower elevations only. The vegetation of Stainmore does resemble that of Upper Swaledale except for the absence of juniper.

Plants, including trees, recorded at very many of the sites (marked * on Table 1) have been listed by LR. Mosses and lichens have not been recorded with the exception of the non-flowering flora recorded by Dr Alan Pentecost on the exceptional tufa formation at the head of the ravine at How Edge Scars.

Preliminary conclusions on the data.

1. Limestone ashwood with and without yew is limited to exposures at Type C and D Localities, on or below the top of the Main Limestone.

2. Aspen has been recorded in the Swale Catchment above the confluence of Arkle Beck at a total of more than 20 sites at all Type Localities. The few aspen records from the lower dale slopes (Type D Localities) indicate that aspen was once widespread at all elevations.

Aspen records are usually for cloned colonies where old ‘mother’ trees and three or four generations of young ramets springing from her roots are present. Regeneration of aspen is only possible when rabbit damage is minimal. Further work is necessary to determine whether these colonies are clones and of single sex.

Elsewhere, aspen has been recognised at Sleightholme Beck on Stainmore, on Deepdale Beck and is widespread throughout UpperTeesdale and also in Lower Wensleydale.

3. Juniper has been recognised to date at more than 40 localities in the Swale Catchment at and upstream of Ellerton Scar and at all Type A-D localities.

4. The prostrate form of Juniper is thought to be present at all or most of the localities, however since this identification has not been formally confirmed by the BSBI, J. communis ssp nana has not yet been formally differentially noted in this record.

5. As elsewhere throughout the Uplands, the junipers which survive in Swaledale are usually single bushes or isolated populations of less than 4 bushes at any one Location. These junipers are not viable and, sadly recent rabbit ring barking has led to severe damage or the death of very many isolated junipers.

6. Juniper has not yet been found on Stainmore within the Greta Catchment but has recently been identified by LR together with aspen in Baldersdale. Both aspen and juniper are widespread elsewhere in Upper Teesdale.

7. No recent record of juniper in Wensleydale exists, (Millward, 1988). It is noticeable that while a scattered population of juniper exists on the low cliffs above Cliff Beck on the Swale side of the Pass below the Buttertubs Road, in contrast, the very similar limestone cliffs of Fossdale Beck just 1km south, across the Swale-Ure interfluve are devoid of juniper.

8. Yews are perhaps the most impressive of the relict woodland trees of the limestone scars of Swaledale and it seems very strange that the similar limestone cliffs of Wensleydale are devoid of yews, most of the high limestone Scars of Wensleydale are barren or of any woodland vegetation for that matter.

The cliff yews of Swaledale are of exceptional value for every reason, both as surviving specimen trees of great beauty and as a resource for future research. Many will, I am certain prove to be of immense age.

This is not the place to expand on their different forms, both multistem and maiden trees of great size and girth exist in the comparative shelter of the lower cliff face and on the top edge of the scree slopes. The cliff edge yews, stunted and many stemmed, are clearly of very great age. I have already recorded and am engaged in recording very many specimen yews and many other cliff trees of all species representative of the cliff trees present on the Woodland Trust ATH Website. Detailed accounts of the woodland fragments in their landscape setting and including photographic portraits of all woodland localities will be made available on the Swaledale and Arkengarthdale Archaeological Society website.

It has become apparent that the cliff yews may be cloned populations. Reproduction from root systems penetrating far through the limestone is likely. For example, at Deepdale above East Applegarth in Lower Swaledale, a quick count of a population of 22 yews comprised 20 berried female trees, one male and one inaccessible tree that could not be identified as male or female.

Finally, the effects on the stability of limestone cliffs from penetration of root systems of large yews is worthy of note. Exposed yew root systems, python like, can be seen to extend across and down the face of many of the limestone cliffs. These large root systems must have once penetrated the massive limestone through very small fissures. Once present these roots expand and completely destabilise the cliff face leading to continuous rock falls and building of scree.

9. Discussion of aspen, juniper and yew should not deflect attention or detract from the significant populations of trees of other species - ash, wych elm, bird cherry, gean, hazel, rose spp rowan, rare rock whitebeam, sallows and other willow species, all present on and below the limestone cliffs and within the waterfall ravines of Swaledale.

10. The risk that yews, alders, elms and other trees will suddenly succumb to virus disease is ever present. For example a large population of yews at West Applegarth includes a significant and growing number of recently dead trees.

This dire situation needs to be monitored under a programme of research from a British University, at local level.

11. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, I shall draw attention to the existence of a extensive and healthy population of large leafed lime trees, Tilia platyphyllos, mostly managed coppice but also self coppiced ancient trees on the face and top edge of sheer limestone cliffs. in the woods of Lower Swaledale. This population is scattered for upwards of 2km on the south facing cliffs eastward from West Applegarth, beyond Willance’s Leap to Whitecliffe Woods. The presence of large leafed limes, Tilia platyphyllos in Swaledale, at the northern limit for this species in Britain was, I believe, first recognised by Professor C.D. Pigott.

Future contamination from planting schemes.

I know that I shall be treading on toes in expressing my view that the planting of inappropriate ‘berried’ shrubs (ie hawthorn) in vast numbers above sheltered ravines with native woodland which includes blackthorn but largely excludes hawthorn will have long term effects which are not understood. The effects of this extensive planting on the native woodlands nearby are uncertain.

As an example of the unforeseen consequences of plantation, may I refer the reader to the limestone cliff at Hooker Mill Hole where a fine population of aspen, juniper (prostrate form) and ancient yews is now (hopelessly) competing for space with a flourishing population of self seeded european larch which originates from a small mature plantation located below the cliff. Larch are fine desirable landscape trees and the plantation was made for admirable reasons probably with no knowledge of the significance of the presence on the limestone cliff above the plantation, of a native refuge for aspen, juniper and yew. The indiscriminate planting of tree species of ‘nursery stock’ of unknown genetic origins all across the Yorkshire Pennines may have similar unforeseen consequences.

Similarly, DNA analysis can now determine the early post-glacial origins of the British Flora. The planting of trees and plants of distant lowland stock of unknown heredity sourced from nurseries competing on price may compromise the present valuable resource of surviving native woodland communities for future research.

The Woodland Localities

Generally

Woodland localities on the Upper Swale and on each of the principal feeder tributary streams within the Parish of Muker will be grouped together and briefly described (to follow) and are summarised as Table 1 (to follow).

Each of the locations detailed have their individual character, each an isolated fragment of woodland vegetation reflecting differing soils derived from abruptly changing geological strata, aspect, aridity and exposure to climatic conditions all of which may vary in the space of a few metres from shelter within steep sided waterfall ravines to the extremes of exposure and aridity on and below the highest Scars. Swaledale offers a fine opportunity to see woodland plant communities which reflect the full spectrum of exposure, and their own hard life history.

It is very clear that the relative accessibility to grazing animals, primarily rabbits, determines the present survival of plant communities at all locations.

It is also clear that isolated small and non viable populations of juniper, yew, wych elm, and other tree species are currently subject to sudden death from several known and unknown causes. The primary aim of this account of isolated woodland communities is to draw attention to the presence of these locations, primarily as fragments of relict woodland, once widespread, which merit the most careful conservation. These localities are significant places in their own right with ancient trees of the highest sculptural and cultural value reflecting their long hard life and now subject to active and severe threats to their continued existence.

I have defined Upper Swaledale advisedly, since the Main Limestone- well seen at Cotterby Scar, the fine limestone cliff above Wainwath Falls, marks the transition from the Visean Limestone Series to the predominantly siliceous Namurian Series of Carboniferous Rock Strata. This transition also marks a change from the potentially calcareous vegetation on and below the Main Limestone to the predominantly acidic vegetation on the base poor cherts, sandstones and mudstone overlying the Main Limestone.

In fact the rock strata of the study area are abruptly and so severely faulted so that the top of the Main Limestone, 345m on Cotterby Scar at Wainwath Falls is at 500m elevation some 5km to the south east at Long Scar, Great Sleddale.

Thus, I have been able to summarise 38 localities on or below the Main Limestone and 22 localities stratigraphically above the Main Limestone. This is work in progress and 10 known localities in Upper Swaledale have not yet been visited. See Table 1.

During this fieldwork it became apparent that strongly calcareous, tufa forming seepages or springs were present at locations with sandstones and mudstone strata, usually just above stream level. Local enrichment from these springs required separate discussion of these sites from the otherwise wholly acidic vegetation- as Type B sites.

Special emphasis is due to the presence of aspen, juniper, willow spp and bird cherry - survivors of pioneering woodland communities, present in Swaledale from early post glacial time.

To follow shortly, as additional to this Introductory Geographical Account :-

1. The Relict Woodland Localities in their landscape setting - a brief description of the woodland fragments on the Upper Swale and at each of the tributary streams of the Upper Swale.

2. Table One: Upper Swaledale - Gazetteer of Sites in the Parish of Muker. | | Geographical area | Stainmore | | Additional Notes | PROJECT SUMMARY:

RELICT WOODLAND ON THE CLIFFS AND WITHIN THE WATERFALL RAVINES OF SWALEDALE

TIM LAURIE

Work in Progress

Records are to be added on a day to day basis.

Initial priority will be to complete the records for Area 1 Upper Swaledale followed by records to

Areas 2-6 in sequence.

Thus, there will be few records in Areas 2-6 at present, but this situation will rapidly improve. Much fieldwork has been completed in all areas.

SUMMARY

This is a short introduction to a programme of current fieldwork designed to record the distribution

of native tree species and woodland fragments throughout the River Swale catchment, west of Richmond.

My intention is to publish a full account of the fieldwork in due course . For comparative purposes, adjacent areas within Wensleydale and the Tees-Greta Uplands (Stainmore) are also included. The area of this survey is very large and with few exceptions has been confined to localities at or above the moorland edge. Woods wholly within improved pastures have been excluded. Thus, the scope

has been confined to woodland localities on or clearly visible from CROW Access Land.

I have been concerned with the recording of Archaeological Landscapes throughout Wensleydale, Swaledale and the Swale-Tees/Greta Uplands (my study area) for almost 40 years and was introduced to the significance of ancient woodland in the Landscape by Andrew Fleming. It followed that no real understanding of the nature of early human activity in the Pennine Uplands (based on hunting and transhumance) was possible without consideration to the contemporary prehistoric woodland environment.

My purpose in undertaking this survey is to place on record the relict woodland vegetation at the remote waterfall ravines and on the extensive limestone cliffs of Swaledale and adjacent areas. These localities can be regarded as refugia for native trees and formerly more extensive woodland worthy of record on aesthetic grounds as the final refuge of specimen trees of great age, of individual character and of many different species. Each locality has unique botanical interest with plant communities reflecting different geology, aspect, aridity, accessibility and economic or, more

recently, modification from planting schemes. Each woodland locality may include specimen trees

which possess an individual sculptural quality which reflects their hard and long life. Although

having enjoyed a fairly intense interest in upland flora throughout my life, I am not a trained

botanist and could not achieve the aims of this survey without the assistance and active participation of Linda Robinson (LR), one of the BSBI Recorders for vc 65. LR has accompanied me on much of the fieldwork and all the credit for the botanical records must be assigned to her.

The survival of native woodland on the limestone scars and in the waterfall ravines of Wensleydale

differs from that of Swaledale and today does not include juniper and only very rarely, yew. Aspen is common at lower elevations only. The vegetation of Stainmore does resemble that of Upper

Swaledale except for the absence of juniper.

Plants, including trees, recorded at very many of the sites (marked * on Table 1) have been listed by LR. Mosses and lichens have not been recorded with the exception of the non-flowering flora

recorded by Dr Allan Pentecost on the exceptional tufa formation at the head of the ravine at How

Edge Scars.

Preliminary conclusions on the data:

While much fieldwork has been completed within the whole of the study area, the following remarks

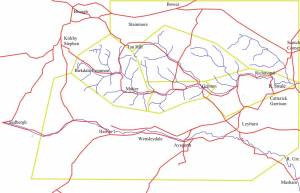

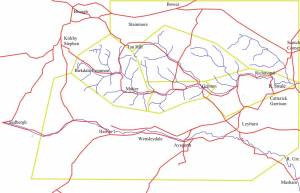

apply principally to Upper Swaledale where records are most advanced. See map.

1. Limestone ashwood with and without yew is limited to localities, on or below the top of the Main

Limestone.

2. Aspen has been recorded in the Swale Catchment above the confluence of Arkle Beck at a total of

more than 20 sites. Aspen records are usually for cloned colonies where old ‘mother’ trees and three

or four generations of young ramets springing from her roots are present. Regeneration of aspen is

only possible when rabbit damage is minimal. Further work is necessary to determine whether these

colonies are clones and of single sex. Elsewhere, aspen has been recognised at Sleightholme Beck on Stainmore, on Deepdale Beck and is widespread throughout UpperTeesdale and also in Lower Wensleydale.

3. Juniper has been recognised to date at more than 40 localities in the Swale Catchment upstream

of Ellerton Scar. The prostrate form of Juniper is thought to be present at all or most of the localities.

4. As elsewhere throughout the Uplands, the junipers which survive in Swaledale are usually single

bushes or isolated populations of less than 4 bushes at any one Location. These junipers are not

viable and, sadly recent rabbit ring barking has led to severe damage or the death of very many

isolated junipers.

5. Juniper has not yet been found on Stainmore within the Greta Catchment but has recently been

identified by LR together with aspen in Baldersdale. Both aspen and juniper are widespread

elsewhere in Upper Teesdale.

6. No recent record of juniper in Wensleydale exists, (Millward, 1988).

7. Yews are perhaps the most impressive of the relict woodland trees of the limestone scars of

Swaledale. The similar limestone cliffs of Wensleydale are devoid of yews, most of the high

limestone Scars of Wensleydale are barren or of any woodland vegetation for that matter.

The cliff yews of Swaledale are of exceptional value for every reason, both as surviving specimen

trees of great beauty and as a resource for future research. Many will, I am certain prove to be of

immense age. It has become apparent that the cliff yews may be cloned populations.

8. Discussion of aspen, juniper and yew should not deflect attention or detract from the significant

populations of trees of other species - ash, wych elm, bird cherry, gean, hazel, rose spp rowan, rare rock whitebeam, sallows and other willow species, all present on and below the limestone cliffs and within the waterfall ravines of Swaledale.

9. The risk that yews, alders, elms and other trees will suddenly succumb to virus disease is ever

present. For example a large population of yews at West Applegarth includes a significant and

growing number of recently dead trees. This dire situation needs to be monitored under a programme of research from a British University, at local level.

10. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, I shall draw attention to the existence of a extensive and healthy population of large leafed lime trees, Tilia platyphyllos, mostly managed coppice but also self coppiced ancient trees on the face and top edge of sheer limestone cliffs. in the woods of Lower Swaledale. This population is scattered for upwards of 2km on the south facing cliffs eastward from West Applegarth, beyond Willance’s Leap to Whitecliffe Woods. The presence of large leafed limes, Tilia platyphyllos in Swaledale, at the northern limit for this species in Britain was, I believe, first recognised by Professor C.D. Pigott.

Future contamination from planting schemes.

I know that I shall be treading on toes in expressing my view that the planting of inappropriate

‘berried’ shrubs (ie hawthorn) in vast numbers above sheltered ravines with native woodland which

includes blackthorn but largely excludes hawthorn will have long term effects which are not

understood. The effects of this extensive planting on the native woodlands nearby are uncertain.

As an example of the unforeseen consequences of plantation, may I refer the reader to the limestone

cliff at Hooker Mill Hole where a fine population of aspen, juniper (prostrate form) and ancient yews is now (hopelessly) competing for space with a flourishing population of self seeded larch which originates from a small mature plantation located below the cliff. See photograph.

The Woodland Localities Generally.

Detailed accounts of the woodland fragments in their landscape setting and including photographic portraits of all woodland localities are available on the Swaledale and Arkengarthdale Archaeological Society website:

Swaledale Woodland Project

Tim Laurie

31 October 2011

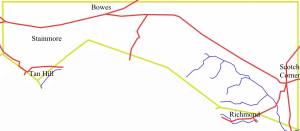

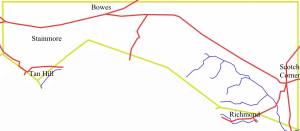

| | Image 1 ID | 1327 Click image to enlarge | | Image 1 Description | Woodland Project Map |  | | Image 2 ID | 1325 Click image to enlarge | | Image 2 Description | Stainmore Section |  |

|

|